15 lakh+ counselling sessions, 900 experts, 300 institutional clients – how YourDOST has grown in the emotional wellbeing spaceRicha Singh, Co-founder and CEO of YourDOST, an emotional wellbeing platform, talks about the company’s growth, its three-pronged approach for corporate organisations, and initiatives during the pandemic.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 has led to several mental health issues compounded by stress, increased responsibilities, loss of jobs, fear of the virus, lifestyle changes, and adjusting to the “new normal”.

Despite the need for intervention, mental health remains a taboo. However, a disruption in offline mental health services has accelerated the demand for services online not just by individuals but also by corporates looking at their employees’ wellbeing.

Richa Singh, Co-founder & CEO, YourDOST

Here’s where YourDOST, an emotional wellbeing platform, has made rapid advances in this space with its multi-pronged approach towards various problems.

The death of a classmate by suicide led Richa Singh, an IIT-Guwahati alumna and a few of her friends, to start Your DOST, an online mental and emotional wellbeing platform, in 2014.

Multi-pronged approach

Over the past seven years, YourDOST has helped individuals and corporates connect to experts, including psychologists, psychotherapists, counsellors, life coaches, and career guides.

Highlighting the impact so far, Richa says, “We have provided more than 15 lakh counselling sessions, have 300 institutional clients and have 900 experts on board. Our clientele includes corporate employees, students, and government projects.”

With corporate employees as its focus, YourDOST has a three-pronged approach to provide diverse solutions.

Richa explains the first step is to unlock an individual’s potential through one-on-one counselling sessions.

“We also offer several self-help programmes that promote self-care through mindfulness techniques, self-help models, self-reflective tools to develop resilience. These will help prevent inertia, burnout or disengagement.”

Curated programmes, for instance, around gratitude, or for women going on maternity leave, internet addiction, etc., also help individuals better themselves.

The second approach is to amplify team performance through communication interventions through training to build more emotionally resilient teams.

“The third approach is to help organisations establish an empathetic culture. If an individual seeks to support, but if the company is not aligned with the idea, it will not impact. We inspect the leadership, how it inspires teams, and what they can learn,” she adds.

YourDOST also works with the government on projects to support students from low-income backgrounds. It also assists the National Skill Development Council to enable young adults to be more emotionally resilient towards their careers.

ALSO READ

Increased engagement

The YourDOST team

Richa believes the pandemic has helped mature the curve faster, with more people talking openly about emotional wellbeing.

According to her, corporate engagement has increased by 400 percent, and YourDOST has facilitated several specialised programmes during both waves of COVID-19.

She elaborates, “During the first wave, companies went through different challenges like layoffs and doing things entirely online. We helped them navigate these challenges. The second wave saw people handle grief, loss of team members, etc. We helped managers support their teams better, especially those impacted by the virus.”

For founders and entrepreneurs, too, the journey has not been easy. “We have seen a 100 percent increase in founders’ engagement because this is an emotionally challenging time for them. It’s lonely at the top. We have a special programme to support them on their journey with individual coaches and specific goals,” she adds.

During this period, YourDOST partnered with the Government of Haryana to run a special mental health helpline for people from low-income backgrounds. The team also trained people to become first responders to make them better equipped to handle dire situations.

Richa agrees that women have borne a large brunt of the pandemic, juggling work and home.

The platform introduced several programmes to support women with relationship issues, raising children, time management, prioritisation, and more.

Richa is happy that there is no more awareness on mental health, given that more people, especially film stars and cricketers, are talking about it.

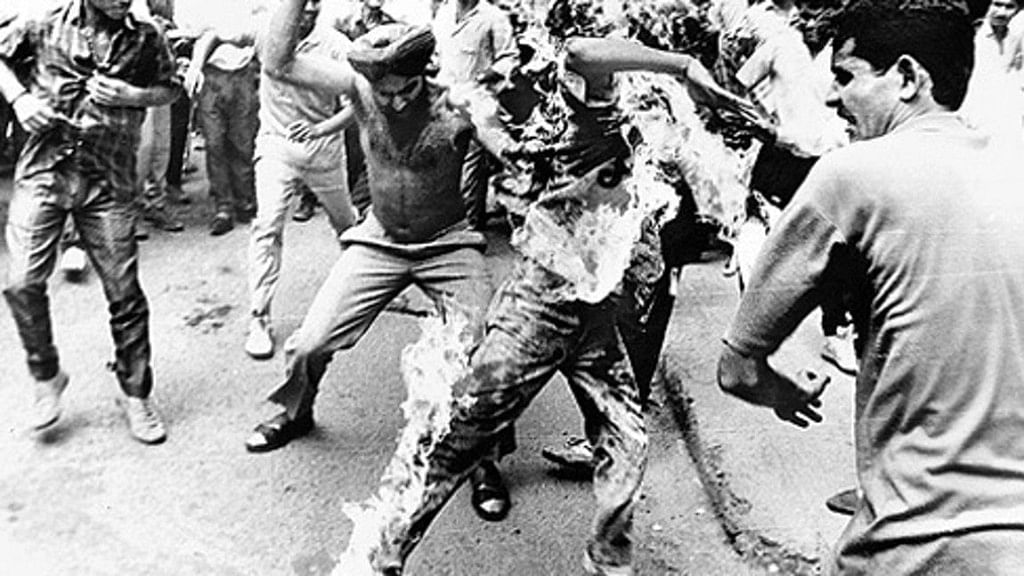

But the situation is not optimistic. “India is first in depression, second in anxiety, and 36.6 percent of global suicides are in India. In a survey conducted during the pandemic, we found that 55 percent of Indians experienced a significant rise in stress levels, including anxiety and anger. Mental health needs to be addressed seriously.”

Richa is modest about YourDost’s achievements. “I think we have just scratched the surface with our numbers. There are a lot more people to be covered in India. We plan to work with more corporate organisations, startups, and others. We want to be at a place where we can take care of the emotional well being of the entire ecosystem of organisations in India and championing mental health and wellbeing,” she says.

YourStory’s flagship startup-tech and leadership conference will return virtually for its 13th edition on October 25-30, 2021. Sign up for updates on TechSparks or to express your interest in partnerships and speaker opportunities here.

For more on TechSparks 2021, click here.

Applications are now open for Tech30 2021, a list of 30 most promising tech startups from India. Apply or nominate an early-stage startup to become a Tech30 2021 startup here.

Edited by Megha Reddy